Death of a Giant: History of GSOB in PQ Preserve

Les Braund and Mike Kelly

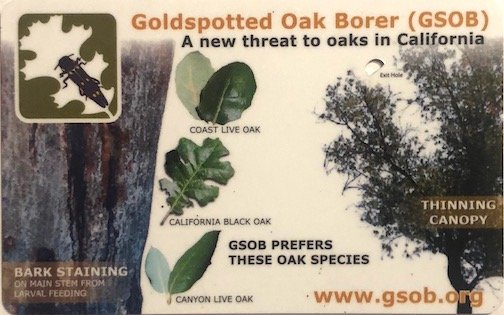

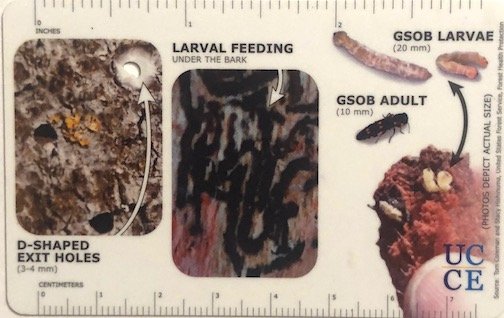

Back in 2018 Stacy McCline of the Del Dios Habitat Protection League, a group we have worked closely with — who was familiar with Gold Spotted Oak Borers (GSOB) — was hiking in the canyon and reported to us that we might have the beetles and should survey for them. A short time later, the City Parks Dept. confirmed this finding. After learning that GSOB was killing tens of thousands of mature Coast live oaks in the Julian area, concern for our oak trees increased. GSOB is thought to have reached Julian in 2004. Mike Kelly, Beth Mather, Les Braund and others took a training class sponsored by the University of California to identify the signs of GSOB. After completion, we were able to properly identify GSOB signs on oak trees. The signs include D shaped boring holes, weeping of sap, cracking of bark, evidence of wood peckers (holes where they bore into the bark after the larvae/insect), and loss of leaf foliage cover. Unfortunately, GSOB prefer large, older trees.

Mike Kelly, Beth Mather, Antonella Zampoli, Anne Fege and I began a survey of the oak trees in the canyon. Unfortunately, we found many trees infested with GSOB. During our survey we discovered a number of very large old oak trees suffering distress, some already dead, with signs of GSOB infestation. There remain hundreds of large, old oak trees in the canyon, some infested with GSOB, most not. A problem for most potential volunteers is that these oaks are usually surrounded by poison oak bushes and often have poison oak vines climbing them! Mike Kelly is immune to it while Les Braund can tolerate a mild exposure, but has to be careful. Other volunteers are highly sensitive to poison oak and couldn’t participate. To see the best diagnostic of GSOB, the tiny 3-4 mm D-shaped exit holes, you literally have to be hugging the oak, putting your hands on it.

Where did GSOB come from?

Les led me to a grove of dead oaks that showed signs of GSOB. From the sheer quantity of dead or dying mature oaks we think that this was the first site within the canyon preserve to be infested. The beetles are not good long-distance flyers, meaning that they came from somewhere close. The most likely source would be firewood from one of the houses on the nearby rim. We think the borers infested the first oaks 3-4 years earlier.

Research has found that firewood is the most common source of beetles in new locations. The firewood in question probably came from Julian. Julian turns out to be the first area in California to be infested, probably a decade or so ago. That first infestation has been traced to firewood imported from Arizona! That’s where GSOB naturally occurs. Up until recently it never successfully crossed the deserts on its own. It came in on firewood and then spread in the Julian area where it has no natural enemies. Tens of thousands of mature Coast live oaks have already died in the Julian area. We don’t know yet whether GSOB’s natural enemies, parasitic wasps, can be imported to southern California.

Surveying 2018.

While surveying we affixed serially numbered blue metal tags to infested trees. We also collected data using the ESRI data collection app, Survey 123. Data included the range and quantity of D-shaped exit holes, the range and quantity of weeping sap spots, cracking bark, woodpecker holes, the percent cover of the canopy, trunk diameter and whether the tree appeared to be dead or not. Survey 123 also allows you to take a GPS reading on each tagged tree. This reading allows you to develop a map of the infested trees displayed over a map of the Preserve and helps you find previously identified trees. We used pink colored tape to mark trail access to tagged trees. Yellow tape meant stay out, bee hive present! This is because the pesticide would harm the bees if sprayed on them.

Once the city confirmed our findings, the Parks Dept. hired Aguilar Plant Care (APC) Company to treat infested trees with a well-known, widely used pesticide called carbaryl. APC is one of only a few pest control companies with extensive experience controlling GSOB. I believe it cost about $17,000. We surveyed the areas to be sprayed ahead of time and developed a plan for when and how to spray. Special permits to use this chemical were obtained from the County Dept. of Agriculture. They notified beekeepers within a specified distance of the spray areas, but no domestic bees forage in the park.

Spray Time.

Peñasquitos Rangers sent out notices, as did the Friends, to social media such as NextDoor warning that certain trailheads and trails would be closed. For the three days of spraying, City Rangers, led by Senior Ranger Gina Washington, mobilized rangers and volunteers while the Friends also mobilized volunteers. Almost everyone set up at trailheads or at barricades at stream crossings and across the main trails with signage about the trail closures. Most of the public stayed away and the few intercepted trail-users complied. Only a few blew past the barriers.

Mike Kelly, being experienced with working with his own spray crews and having visited 90% of the trees, went with the spray crews each day, using both printed and digital maps as well as personal memories to guide the crews in and out of the trees. Spraying was not restricted to infested trees. Large trees near tagged trees were also sprayed. About 6-10 feet of an oak’s trunk(s) was sprayed around the circumference.

When the adults emerge from the cambium layer where they had developed from larvae, they contact the herbicide and die. Adult beetles flying in from elsewhere die when they land on the sprayed bark of the trunk. Two inspectors from the County Dept. of Agriculture accompanied the spray crew the first day. They first inspected the APC crew and their equipment for any safety issues (finding none). They were particularly focused on the safety of any bees that might be out foraging. Anytime we encountered flowering plants we checked for foraging bees. We didn’t find any during the day, perhaps because it was overcast much of the day!

2019 Season.

Surveys occurred, but spraying did not due to problems with the City’s procurement process.

2020 Season.

We learned that the City Parks Dept. couldn’t afford to pay for the spraying. The Friends Board decided to spend our own money to spray the oaks. The cost was a little over $17,000. We hired APC for the spraying again and we and the City Rangers once again mobilized to close the trails, educate the public, and guide the contractor through the park.

2021 Season.

Again the City Parks Dept. was unable to allocate the funds so the Friends stepped in again and paid about $16,400 for APC to spray.

During our surveys we found a number of large oak trees. We paid special attention to the apparently largest tree in the canyon, an oak tree just East of Carson Crossing near the creek. This tree was already infested with GSOB so we requested Aguilar pay special attention to this tree in an attempt to save it. This spring when we surveyed the canyon for spraying, the tree was hanging on. The tree still had green leaves near the top. By this fall the tree appears to be completely dead. Braund measured the circumference at about eighteen feet; the diameter at breast height was about six feet.

We’re sure the skeleton of our Giant tree will be around for a number of years but it is a loss for those who love oak trees. Should you get a chance to look at the tree you’ll notice how majestic it was.

2022 Season.

We’re going to step back and assess our work to date. Casual observations of our oaks have us thinking that we’ve decreased the spread of the beetles and the number of oak deaths. But we want to take a more scientific approach. At the height of new growth this winter/spring we’ll form teams and visit a selection of randomly chosen tagged trees and take more data with our Survey 123 smart phone apps. We will use the bright green color typical of new growth tips on branches to assess the health of the tree. That’s where GSOB impacts are often most evident. We’ll compare this data set with our previous surveys to see if our efforts are having a real impact.

Because of the high cost of spraying and our declining funds combined with the City’s budget not including spraying we will try a new strategy of identifying “hot spots.” Hot spots are where there are clusters of infested trees, perhaps including several dying or dead trees. The latter are often “amplification trees” with large numbers of beetles breeding and laying eggs. Larvae burrow through these trees and eat the cambium. Once the cambium is damaged enough the tree will die. Mature beetles then burrow out, leaving behind D-shaped exit holes, and fly to find new mature Coast live oaks to infest.

We’ll probably plan to focus more limited spraying on these hot spots, thus saving funds for future spraying. In the long run the hope is that a natural enemy such as a parasitic wasp can be imported from Arizona to bring a balance between the beetles and trees, reducing tree mortality. One caveat, however, is that there is some evidence that the Live oaks in Arizona, having co-evolved with the beetles, may have developed a genetic based resistance to the beetles which our trees don’t have.

GSOB is present in an increasing number of parks and private properties all over the county, including Marian Bear Park where it has decimated the old oaks and Daley Ranch.

There is a lot of information online, just search GSOB or gold spotted oak borer. UC Riverside is a particularly good source of information on these beetles.

Image 1. Giant dead Coast Live Oak near Carson’s crossing. Photo by Fred Buenavista

Image 2. Gold Spotted Oak Borer. Male on the left; female on the right. Photo by UCANR.edu

Image 3. Front-side of an identification card we use in the field. Note the small size of the D-shaped exit hole.

Image 4. Back-side of the identification card we used in the field. The small D-shaped exit hole is also visible.